Clash of the Cups: NHL Sues Over Stanley Cup Beer Mug

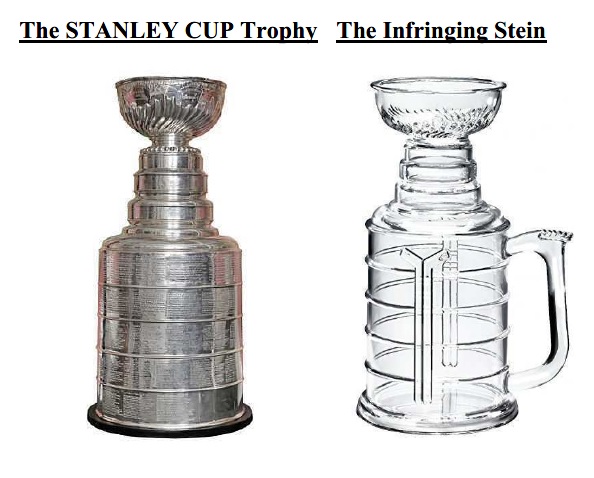

July 26, 2018—Even in July, with the heat of summer still blazing, you can’t get away from ice hockey in Minnesota. However, now that the Vegas Golden Knights have settled their dispute with the U.S. Army, it was starting to look like we were running out of hockey trademark news. Thankfully, the National Hockey League came through at the last second, filing a trademark infringement lawsuit on July 23. At issue is the NHL’s rights in the design of its championship trophy, the Stanley Cup, and the defendants’ sale of allegedly infringing beer mugs shaped like the Stanley Cup.

The defendants comprise companies, purportedly all owned or managed by the same individual, operating primarily under the name “The Hockey Cup LLC.” According to the complaint, the Hockey Cup has been selling unauthorized reproductions of the Stanley Cup as well as counterfeit jerseys. The company even applied to register trademarks for THE CUP HOCKEY. The NHL opposed the applications and, in response, the Hockey Cup counterclaimed to cancel the twelve registrations asserted by the NHL on the grounds of lack of ownership, abandonment, non-use, and fraud. With the gloves now off, the NHL chose to escalate the skirmish and sue the Hockey Cup in the Southern District of New York for trademark infringement, false association, dilution, copyright infringement, and unfair competition.

There is a good chance that the Hockey Cup will also assert its counterclaim for cancellation of the NHL’s registrations in the lawsuit. The counterclaim essentially argues that the NHL does not control the actual, physical Stanley Cup, and therefore the NHL cannot have trademark rights in the design of, or name of, the Stanley Cup. Strangely enough, this part of the argument has some truth to it. Since 1893, the Stanley Cup has been controlled by a pair of trustees. In 1926, the Trustees reached an agreement with the NHL, and the NHL has been the sole organization associated with the cup ever since, with continued permission from the Trustees. If that’s true, the Hockey Cup’s claims appear to be a bit of an underdog in this legal matchup.

But does the Hockey Cup’s sale of beer mugs in the shape of the Stanley Cup create a likelihood of confusion with the NHL? The NHL claims in its complaint that it has sold beer mugs in the shape of the trophy in the past, but none appear to be available at the moment. The NHL is selling Stanley Cup shaped ornaments, paperweights, inflatable trophies, miniature crystal replicas, and, for some reason, a popcorn maker. If we’re sticking with the booze, the NHL is selling a shot glass with a picture of the Stanley Cup. But yet, no beer mugs in the shape of the trophy.

To prevail though, the NHL does not need to show that it has lost sales due to the defendant’s conduct. Instead, there must only be a likelihood of confusion as to source, sponsorship, connection, or affiliation. One plausible argument in support of the NHL’s claim is that consumers will mistakenly assume that the mug has been licensed by the NHL.

In fact, one recent case from the Eleventh Circuit is quite relevant to the dispute. In that case, the Savannah College of Art and Design, Inc. sued an unauthorized online manufacturer and seller of apparel that was selling clothing with the school’s name. Savannah Coll. of Art and Design, Inc. v. Sportswear, Inc., 872 F.3d 1256 (11th Cir. 2017). The school sued, but the school could not establish that it began selling apparel with the school’s name before the defendant. Based on this, the district court concluded that the school’s rights in the mark with respect to education services did not provide it with trademark rights in the name for clothing. The district court granted summary judgement to the defendant.

On appeal, the Eleventh Circuit reversed, relying on precedent involving – you guessed it – hockey:

One of our older trademark cases, Boston Prof’l Hockey Ass’n, Inc. v. Dallas Cap & Emblem Mfg., Inc., 510 F.2d 1004 (5th Cir. 1975), controls, as it extends protection for federally-registered service marks to goods. Although Boston Hockey does not explain how or why this is so, it constitutes binding precedent that we are bound to follow.

As the quote suggests, the Eleventh Circuit is not certain that the precedent was rightly decided. In that decision, the NHL and the Boston team sued a manufacturer to prevent the sale of patches featuring team names and logos. The NHL had registered the marks for hockey game entertainment services, but not for any goods. The court noted the decision has been criticized but never overturned. As a result, the Eleventh Circuit remanded to the district court for further proceedings consistent with the Boston Hockey ruling. The NHL—and any other school, sport team, or other organization with an appreciable amount of merchandising—will want to pay attention to the resolution of the case, and consider filing applications to register their marks for valuable, merchandised products.

In the meantime, we’ll watch the ownership dispute play out between the NHL and the Hockey Cup. While it appears to be a longshot, perhaps ownership of the cup will return to the people of Canada, as some prefer (mostly Canadians). Until then, we’ll leave you with the words of Lord Stanley himself, announcing the creation of the Stanley Cup in 1892: